When prolonged drought occurs in East Texas, especially during the growing season, pine beetle activity is likely to increase.

You can expect to experience a significant drought at least once during the life of a pine pulpwood stand and potentially twice during a sawtimber rotation. Pine trees growing in shallow soils or with high concentrations of clay are especially vulnerable to moisture stress during droughts.

Fire, hail, ice, lightning, wind, standing water, disease, logging, and other disturbances that increase the stress experienced by your pines may make them more susceptible to pine engraver beetle attack.

Pine engraver/Ips bark beetles

Ips bark beetles, also known as pine engraver beetles, are small, cylindrical insects ranging from brown to black in color that feed on and lay eggs in the inner bark of pine trees. Engraver beetles don’t usually kill a significant number of pine trees. Instead, they usually breed harmlessly in fresh logging debris and weakened trees.

Almost any pine that’s particularly advanced in age may be susceptible. But when several trees in a small area are weakened or stressed due to drought or other disturbances, Ips beetle infestations may result in increased mortality. Pine engraver beetles (or Turpentine beetles, for that matter) are rarely the sole cause of a tree’s death. Instead, they are generally a signifier that a tree is already weakened or dying or one of many factors leading to a tree’s death.

Ips beetle activity is consistent year-by-year, though attacks are usually fairly scattered geographically, and usually only a few trees are involved in each infestation. Stands that experience increased droughts, die-offs due to fire damage, storm damage, or other disturbances are more likely to see pine beetle incursion and increased mortality.

In extremely rare cases, it’s possible for Ips to infest a thousand or more trees in succession within a relatively short period of time, particularly on the western fringe of pine habitat in Texas or in stands exposed to chronic environmental stressors. These trees can live in a perpetual state of stress and drought, and be more susceptible as hosts for beetles because of it. However, even in these marginal conditions, not all infested pines will die.

Engraver beetles include three separate species that all infest and kill southern yellow pines. They are differentiated by the number of spines on each side of their abdomen, and the portion of tree their species colonizes.

- The eastern six-spined engraver beetle, Ips calligraphus, is about 5 mm long and tends to inhabit large-diameter material, like a tree’s trunk or large branches.

- The eastern five-spined engraver beetle, Ips grandicollis, is about 4 mm long, and is usually found in medium-sized material like the upper trunk and large branches or in small diameter trees.

- The small southern pine engraver, Ips avulsus, is about 3 mm long, and is almost always confined to branches in the tops of trees.

It is not uncommon to find all three species in a single tree. If only the small southern pine engraver attacks a tree, the top portion of the crown may die, while the lower limbs remain alive. However, even these trees may eventually experience mortality.

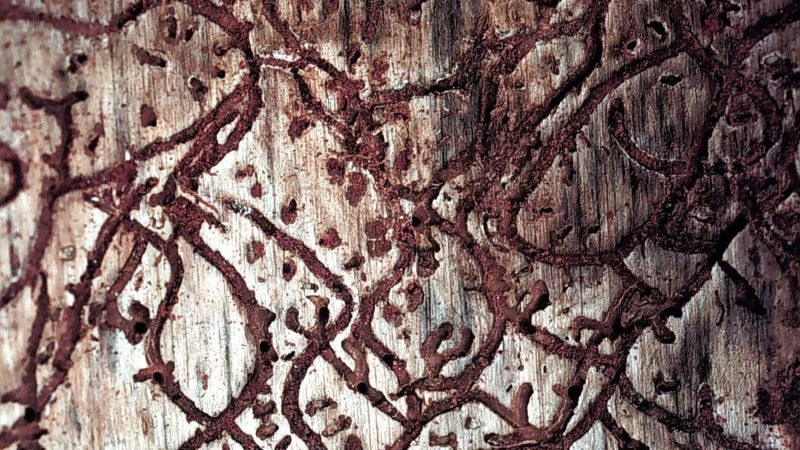

The three species of engraver beetles construct distinct vertical-oriented galleries and tunnels generally in the shape of the letter “Y,” “H,” or “I” as they lay their eggs in the inner bark, and the small southern pine engraver will also construct unbranched, “I” shaped gallery. As the beetles construct these egg galleries, the pattern is etched on the inside of the bark as well as the outer sapwood of the tree. The presence of vertical galleries in the shape of “Y,” “H,” or “I” is the easiest way to identify engraver beetle attacks. These galleries may range from an inch or two to over a foot in length.

Black turpentine beetle

Another pine bark beetle of concern in east Texas is the black turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus terebrans. This beetle readily responds to fresh pine sap (resin) associated with injured trees. Like the three species of engraver beetles, the black turpentine beetle is not usually a serious problem because their typical attack pattern is to infest scattered trees.

The turpentine beetle is commonly found in stumps, injured trees associated with logging activity, and trees damaged by fire. They are also common in suburban settings where tree injuries may occur due to new construction, poorly timed pruning, and root damage. While they don’t have an easily identifiable pattern in the galleries they create in the inner bark of their targeted pines, they will generally only attack the bottom six to eight feet of any particular tree.

Southern pine beetle

The Southern pine beetle, Dendroctonus frontalis, is the most damaging native insect pest in U.S. southern forests. For a long time, it was one of our agency’s top concerns, right next to wildfire mitigation.

In small populations, they behave very similarly to pine engraver beetles or black turpentine beetles in their favoring of injured or stressed pines as host trees. However, as the infestation builds in size, they can exponentially spread to nearby otherwise healthy pines, potentially leading to a mortality event that could encompass hundreds or even thousands of acres.

There have been no reported cases of southern pine beetle in the state of Texas since 1998. We take great care as an agency in monitoring for their return. Chances are that if you’ve found evidence of a beetle infestation on your property, it isn’t southern pine beetle.

When they do infest pine trees, they create winding “S” shaped galleries that are distinct from those of engraver and turpentine beetles.

Impacts

It is important to determine which of the three kinds of bark beetle mentioned above has attacked a tree. All will chew holes through, feed, and lay eggs in the inner bark or cambium (the area between the bark and the wood) of a tree. Bark beetles, however, do not bore into the wood of the tree.

It’s a good idea to remove some bark from a recently attacked tree to look for the distinct gallery pattern made by the adult bark beetle, since all five of the pine bark beetles are quite small and can easily be confused with other insects found in dead pine trees.

One of the first signs of attack by engraver beetles is the presence of frass; reddish-brown boring dust created by the beetle as eats its way through the bark. The frass may build up in the crevices of the bark, or near the base of the attacked tree. You might also see bore holes- the entry points of the beetle, usually no wider than the diameter of a pencil lead.

When a tree has a good supply of moisture, it may form a glob of resin extending out from the bark called a pitch tube, as it tries to protect itself from beetles boring through the bark. These are sure signs of beetle attack. Pine engraver beetles tend to attack the tree on the flat bark plates, forming pitch tubes with a reddish-brown appearance as the frass mixes with the resin. Southern pine beetles tend to attack in the crevices between the bark plates, and their pitch tubes are generally a creamy white color.

Pine engraver beetles aren’t the only kind of pest that create pitch tubes on pines, though. Pitch tubes from black turpentine beetles are much larger and are usually purplish or whitish in color, but only on the lower few feet of the trunk. However, during periods of drought, pitch tubes may not form on the bark of the trees and only the frass and bore holes will be visible. Southern pine beetle pitch tubes are smaller and usually have a whiter hue to them. Some foresters compare them to looking like miniature pieces of popcorn.

The next visible characteristic of attack will be the foliage (needles) of the tree turning from green to yellow to red. During the heat and drought typical of late summer in east Texas, an infested tree’s foliage may turn from green to red in around three weeks. Comparatively, the needles of a beetle-killed pine in the winter may remain green for two months or even more, because of the cooler temperatures and higher moisture. Once the needles turn red, the tree is dead and cannot be saved.

“If the needles are red, the tree is dead.“

Pine trees that have been attacked by pine beetles were likely already stressed or dying, and unlikely to recover. Pine engraver beetles can also sometimes attack only the upper portion of the tree and kill the top but have yet to attack the lower portion of the tree. In those cases, it may be impossible to spot pitch tubes or frass, making diagnosis difficult.

Life cycle

As the engraver beetles construct their egg galleries underneath the bark, the female beetles will lay eggs along the sides of the gallery. From these eggs small, white grubs hatch that feed on and then pupate within the inner bark. When the pupae mature, they transform into new adult beetles. The new adults then chew a small, pencil lead-sized round hole in the bark, emerge, and fly in search of another tree to attack.

During the summer months when daily temperatures consistently reach the 90s, the time from an egg becoming a new adult beetle (one generation) may be as short as 21 days. Overlapping generations of beetles occur such that all stages of the beetle are always present. East Texas typically sees five generations of bark beetles every year. When temperatures drop to the 50’s or below, very little beetle development and activity will occur.

Control

In a forest stand, responsible management practices also tend to be good beetle prevention practices. Direct control is rarely needed for an infestation of engraver beetles in a forested environment. If only a few trees have been attacked, doing nothing is often an acceptable choice. If active control is deemed necessary, though, cutting and removing the infested trees from the property is the best course of action.

Felling the trees and leaving them in place, like one may have done for controlling the southern pine beetle, is counterproductive. In addition, removing trees that the beetles have already emerged from isn’t necessary, nor is cutting down a radius of green, healthy trees around the infested trees.

For protecting pines in your yard from pine engraver beetles, maintaining healthy trees is still the best way to mitigate risks of infestation. Root damage caused by construction and drought are the two most common stress factors for the pine trees in your lawn. Watering trees slowly and deeply during periods of drought and reducing risks of soil compaction around your trees’ roots and avoiding damage to root systems are your best and easiest means of preventing pine engraver beetle attacks.

Visibly infested trees that contain some life stage of the pine beetle should probably be removed, but you should ask the opinion of a forestry professional before making such a decision. If a beetle-killed tree is removed, care should be taken to not damage the other, un-infested pine trees present on the property. Trees wounded in this manner will be more vulnerable to attack by pine beetles. As in a forest stand, removing trees from which the engraver beetles have already emerged is not necessary unless the dead tree poses a safety risk.

If the dead trees are positioned so that they could eventually fall on structures, roads, power lines, fences, or so on, they should be considered hazardous and removed. It will generally take six to ten months after a pine tree dies for it to decay enough that large limbs, the top, or the trunk may break, but it is safer to remove dead pines in dangerous positions sooner rather than later.

Insecticides

We will rarely recommend that landowners treat for pine engraver beetles, and instead generally suggest that you let the beetle infestation run its course, or to preemptively cut the infested tree(s) down before it dies and potentially becomes more dangerous as it rots. It is generally cost-prohibitive to chemically treat for beetles at a stand-level scale, and usually isn’t necessary, so long as responsible forestry management is practiced. As such, treating trees with insecticide to prevent beetle infestation is usually reserved for singular trees of special value to their owner.

In these specific cases, use of insecticide may be effective in prevention and control. Systemic insecticides can be very effective in controlling bark beetles and are generally applied via either a soil-drench method or direct injection into the trunk. Soil-drench applications are usually less expensive, require more frequent applications, and take longer to be absorbed into the tree through its roots, which can delay protection. Direct injection of insecticides is more expensive because of the specialized equipment that’s utilized, but applications are required less frequently, and absorption occurs much more rapidly. Not all chemicals and not all formulations of chemicals are created equal. You should consult with your local forester to learn about the most current, effective treatment options.

Spraying insecticides on your pine trees for controlling bark beetles is largely ineffective, due to the lack of exposure to the infesting insects. For it to be effective at all, the entire tree must be sprayed, so that the insecticide can soak through the bark, but this is largely impractical. Spraying for bark beetle control is not recommended.

Other considerations

During the fall, it is natural for pine trees to develop small “flags” of yellow and red needles scattered through the crown of the tree. Also, discoloration of the second-year needles (needles away from the end of a branch) occur in the fall and during drought stress.

These needles may persist on the branches, and needles that drop from upper branches may lodge on lower branches. This tends to give the tree’s foliage an off-color or unhealthy appearance. In addition, an entire branch in the lower crown (usually a bottom branch) may die in the fall of the year. This is normal and does not indicate that pine bark beetles are beginning to attack the tree.

In these instances, the casual observer may mistakenly think the tree is succumbing to pine bark beetles. However, if the upper third or half of the tree’s crown turns red, or all the needles have turned red, it is likely to have been attacked by pine engraver beetles. Because of the sometimes-confusing color pattern of pine needles in the fall, you should be cautious about assuming you have an epidemic of engraver beetles in your trees or timber.

There are two common insect associates of pine bark beetles. Ambrosia beetles are responsible for the fluffy, white sawdust that is often seen around the base of a dead or dying pine tree. These small beetles (about 3 mm long) bore into the sapwood of the tree. Ambrosia beetles are not responsible for killing the tree, but when their white sawdust is present around the base of the tree, the tree is probably dead.

The second common associate of pine bark beetles is a round-headed borer commonly called a sawyer. These beetles are attracted to pine trees that are very weak or recently dead. The adult beetle is about ½-inch long, has a mottled brown color pattern, and has antennae at least as long as the body. The female will lay her eggs in a small cone-shaped pit she chews in the bark. The larvae (or grub) will feed between the bark and the wood for a period of time and then bore into the sapwood of the tree. On a still, warm day, it is not uncommon to hear a rhythmic chewing or crunching sound made by the larvae of the sawyer as they feed. Mature larvae may reach a length of two inches. No controls are necessary or recommended for either ambrosia beetles or sawyers as the tree is dying.

Ips bark beetle activity can be widespread in East Texas during times of drought, impacting many landowners. Closely watch your trees and their pine stands during periods of drought. If engraver beetles attack, direct control may be warranted.

Incorrect information about engraver beetles tends to abound in drought situations. You may be told you need to cut all pine trees before the pine beetles kill your trees. This is very rarely true. Exercise caution before cutting pine trees because of suspected pine engraver beetle attacks.