During the WWII, TFS lost many lookoutmen to the draft—men who maintained the 3,000-mile telephone system. In search of a better approach to wildfire detection, the agency began the experimental use of rented, fixed-wing aircraft; W. T. “Bill” Hartman, Bruce F. Stewart, and Maurice V. Dunmire led this effort.

In 1943 following the successful trial, TFS purchased a secondhand 65-horsepower Piper airplane for aerial detection, housing the craft at the Lufkin airport.

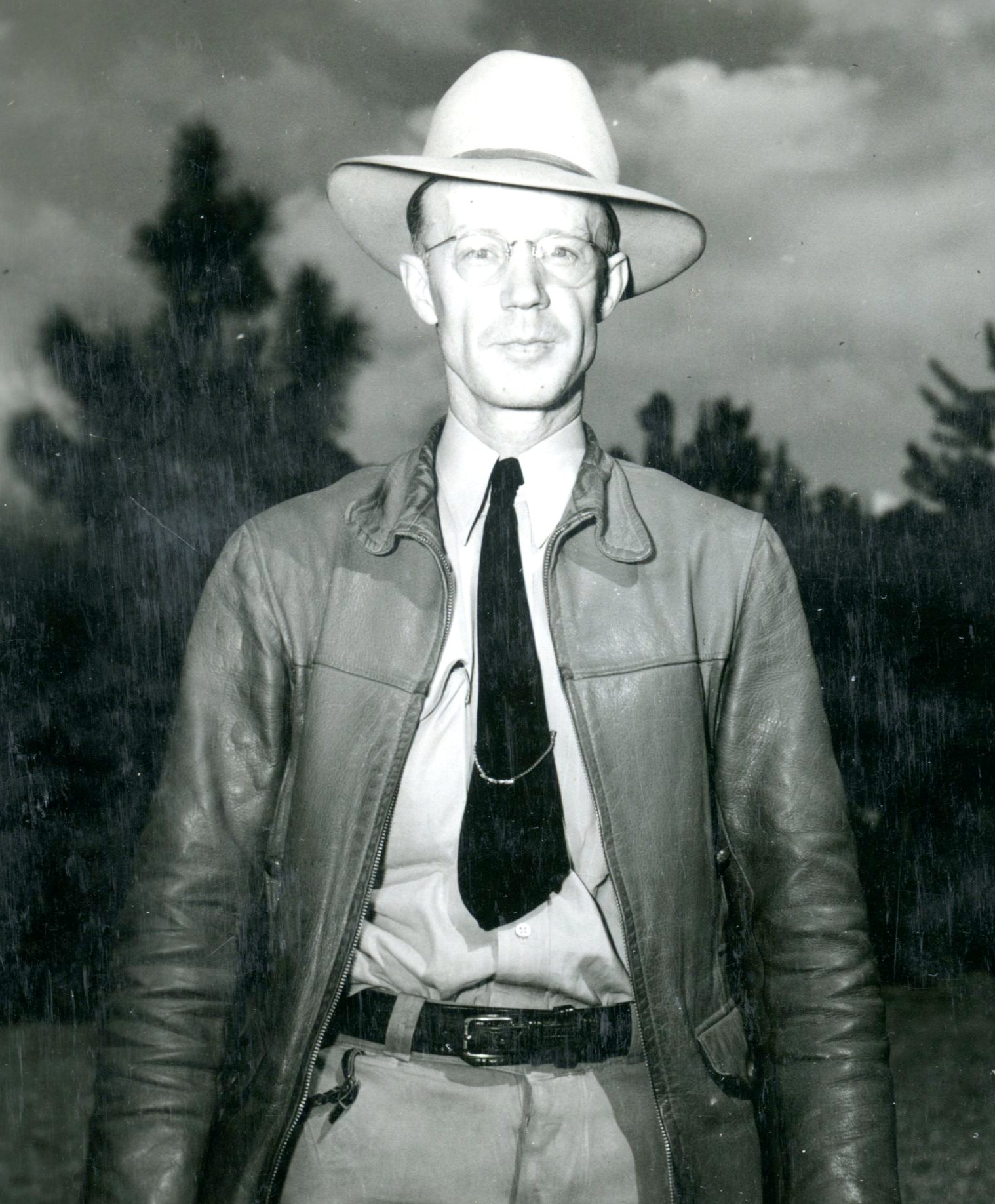

The red-painted, high-winged plane was named Smoke Chaser No. 1 and was flown mostly by Chief Pilot P. R. “Peter Rabbit” Wilson and Hartman, a TFS forester who had become a pilot following just six hours of flight instruction. Hartman was largely responsible for involving Civil Air Patrol (CAP) pilots in fire detection over East Texas during the war as a means to supplement the TFS airplane.

During the three years when the CAP, Texas Forest Patrol was in operation, approximately 122,000 miles were flown on 474 missions and a total of 1,705 fires were reported by two-way radio. The aerial fire patrol operations in Texas had gained nationwide recognition by the time TFS planes and pilots essentially took over the aerial patrol duties in East Texas in 1948. In that year, TFS operated three patrol planes, one each out of Lufkin, Woodville, and Kirbyville, while CAP squadrons were temporarily reactivated out of Bryan and Palestine for fire patrol of forested fringe areas.

Airplanes proved superior to fire towers for early detection of wildfires, especially on days of poor visibility. To compare efficacy, TFS crews set fire to oil drums full of fuel at selected locations unknown to the pilots or the towers. Invariably, Hartman recalls, the planes found the smoke before the towers did. They also had the advantage of immediate investigation. A voice-powered megaphone installed in the side of the fuselage allowed conversations with ground crews. Wing and hand signals also were devised.

After the war, TFS purchased a fleet of five Globe TEMCO Swifts. According to Hartman, the Swift was ideally suited for fire detection. They cruised at about 145 mph and could easily cover a TFS district in 30 minutes flying in a grid pattern at 3,000 feet. As if he were flying a dive bomber in World War II, the pilot would put the Swift into a steep dive to lose altitude so he could take a closer look at the source of smoke. Wildfires were reported on a grid basis to the district office and crew(s) dispatched if needed. During a busy wildfire season, each plane reported and investigated a smoke every six minutes on average.

TFS maintained two airplane hangars to house and maintain its fleet, one at the Lufkin airport and a second on the airstrip in Kirbyville. TFS found home grown pilots were preferred to fly the detection planes. Most of the pilots returning from the war had no forest experience and could not always do the job outside flying. “We did a lot of the training of our own pilots at the Conroe airport, an ex-military field with long, wide runways,” 97-year-old former TFS pilot Bill Hartman recalls. “One of our foresters wanted to fly, and tried hard, but never could. I can still see him landing, losing control, going down the runway sideways with tires screeching blue smoke, then winding up like a top in a ground loop spin.”

The advent of small aircraft for fire detection would render the fire tower obsolete by the early 1970s, much like the mechanized skidders and loaders had essentially done for the mule and ox in logging operations by the 1920s.